The earliest settlement of what is now Avoch was on the flat land near the mouth of the burn – where the Henrietta Bridge now stands. The confused layout of the old cottages known as The Dock is some of the earliest fisher housing, and is best explored on foot – the streets are very narrow and not suited to modern transport. The small parallel streets to the east of The Dock (known as “the streeties”) bear the family names of the Mackenzie lairds of Avoch – John Street, James Street, George Street, Margaret Street. Just across the burn mouth lies another row of low white-walled fisher cottages.

The main industry of the area was fishing. The firth itself provided much of the local living. Herring appeared regularly enough to provide important winter fishing, known as the “kessacks” or Kessock Herring. Sprats similarly shoaled in enormous quantities within the confines of the firth, and this “garvie” fishing was also an important feature of the village’s seasonal round.

With life at subsistence level, families had little in reserve. The Ross-Shire Journal of 1883 reports that the Avoch minister had received a gift of money to be distributed among the most destitute of the village following the almost complete failure at that time of the herring and garvie fishing.

The smallest fishing boats of the village were the “skufteys” which were used close to shore, often by the older men. They were a useful means of ferrying back and fore people and goods to larger boats lying off-shore. A combination of Black Isle larch and local skill produced the clinker-built “scaffies” – a brown lug sail completed the picture of a finely proportioned craft that was for long the mainstay of the fleet.

At the end of the winter herring fishing, the round-stemmed scaffies were hauled up out of the water and sometimes right into the burn mouth. The long summer days would see the little boats fishing away from home along the north coast in Caithness or over in the west around Loch Broom.

Larger boats, particularly the Zulus, introduced just across the Moray Firth, became the mainstay of the fleet, and opened up new possibilities for summer fishing – to follow the shoals of fish from Shetland down to Caithness and Buchan, then farther south to the English waters of Lowestoft and Yarmouth. The fisher lassies followed the fishing south, with their wooden “kistacks” filled with their most necessary possessions. When the fishing was at its peak, the young women gutted the fish and packed the herring into wooden barrels,

Apart from net fishing, there was also some setting of cod nets around Tarbat Ness in Easter Ross, and of baited lines for white fish in the same area. Mussels and lug worms were gathered around Munlochy Bay and transported back to the village, where the mussels were shelled and the baited hooks carefully arranged in a flat container called a “skoo”.

In time, the larger ports along the Moray coast and on the North-east knuckle began to forge ahead with their large fleets of steam drifters. Lossiemouth, Macduff, Fraserburgh and Peterhed emerged as main centres of the fishing industry, while the smaller villages with difficult harbours declined. But while nearby Cromarty failed altogether as a fishing centre, Avoch continued – a fact due less to the quality of its harbour than to the acumen of the men who sailed from it.

The Avoch community was close-knit. A small number of surnames existed in the village – Patience, Jack and MacLeman. With so many sharing the same surnames, by-names were a necessity to avoid confusion.

Avoch also had (and still has) its own local dialect. Incomers find the local speech difficult to understand. The archaic use of “thees” and “thous” is only one difference Avoch speech is liberally scattered with diminutives – a boy for example, being a “shelee” (North East “chiel”), and a girl a “deymak”.

In the late 1920s there were still well over 200 village fishermen. All that remains today of the days of sail are some fading photographs and a few blackened Zulu ribs sticking out of the Munlochy Bay silt – for this was a traditional last resting place for the old boats when all the useful pieces had been stripped from them.

The village, like most fishing communities, was not without its disasters. “The drooning” happened in 1871, when some young women were being ferried out to a boat which was to take them to Inverness to sell their fish to the town housewives. A swell caused the small boat to toss about, and panic set in. Fearing for their safety, the women rushed to one side of the boat, causing it to overturn and pitch them into the sea. Fourteen women perished, some leaving young families. The gravestones in the burial ground of the parish church serve as reminder to this day.

Extract from “The Black Isle”, by Douglas Willis, Published by John Donald Publishers Ltd. Photographs copyright of the Avoch Heritage Association.

The Sea and the Land

Avoch is surrounded by the fields of Knockmuir, Arkendeith, Rosehaugh Mains and Muiralehouse farms. The extensive woodlands of Rosehaugh and Avoch estates have survived and add greatly to the variety of the landscape and wildlife of the area.

The rich farmland near Killen rises gently to the Mulbuie ridge (maximum height 800ft) which is now nearly all covered with coniferous forest.

Mulbuie was once open moor common land, to which all had access for grazing livestock and for peat, but it was divided up between neighbouring estates in 1828.

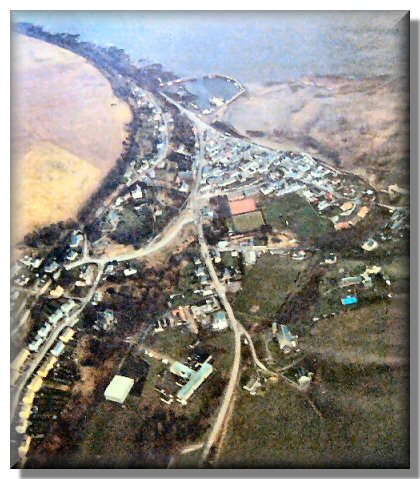

Below – aerial view of Avoch towards the harbour.